CSA Marine Corps

Once a Marine, always a Marine!

When a young person joins the Marine Corps, they take an oath to defend the Constitution and their country from all enemies foreign or domestic. In 1861 they faced an enemy unlike any in their history. This time the enemy was domestic. The President of the United States declares war on his own country in order to take authority away from the states and increase revenue with the collection of taxes.

The Confederate States Marine Corps (CSMC) was a branch of the American Confederate States armed forces during the Abraham Lincoln War. Established by an act of the American Confederate Congress on March 16, 1861.

The manpower of the CSMC was initially authorized at 45 officers and 944 enlisted men, and was increased on September 24, 1862 to 1,026 enlisted men.

The organization of the Corps began at Montgomery, Alabama, and was completed at Richmond, Virginia, when the capital of the American Confederate States was moved to that location.

The CSMC headquarters and main training facilities remained in Richmond, Virginia throughout the Abraham Lincoln War, located at Camp Beall on Drewry’s Bluff and at the Gosport Shipyard in Portsmouth, Virginia.

The United States Marine Corps had been an “exceptionally fine and well-disciplined” organization. From it came the nucleus of the establishment of the American Confederate Marine Corps. The CSMC was modeled after the USMC, but there were some vast improvements: the American Confederate Marine Corps organized themselves into permanent companies, replaced the fife with the light infantry bugle. When ashore they provided guard detachments for American Confederate naval stations at:

- Richmond, Virginia

- Camp Beall, located near Fort Darling at Drewry’s Bluff, Virginia

- Wilmington, North Carolina – Fort Fisher

- Charlotte, North Carolina

- Charleston, South Carolina

- Hilton Head Island, South Carolina

- Savannah, Georgia

- Pensacola, Florida – (manned naval shore batteries)

- Mobile, Alabama

Seagoing detachments served aboard the various warships and even on commerce destroyers.

Once the states severed bonds with the Lincoln government, most of their native sons followed suit. Nearly one-third (20 of 63) of its officers in the USMC left. Of those, 19 served as the principal architects and leaders of the newly created American Confederate States Marine Corps.

The CSMC had the most promising and brightest officers, and many from Virginia. First Lieutenant Israel Greene was perhaps the best known Marine at the time because he had led the company of Marines who subdued that lunatic terrorist John Brown and his followers in 1859 at Harpers Ferry. There was Captain George H. Terrett, had distinguished himself at the battle of Chapultepec in the Mexican War. And still another Virginian and hero of Chapultepec was First Lieutenant John D. Simms, who, along with First Lieutenant Julius E. Meiere of Maryland, would see action at the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff.

The Battle of Drewry’s Bluff

On Mary 15 th 1862 , the Galena had been the lead vessel of a Lincoln navy squadron ordered to steam up the James river, disable American Confederate batteries along the shoreline, and bombard the civilians in the city of Richmond Virginia. But the fleet never got past Fort Darling, situated on Drewry’s Bluff, some eight miles below Richmond Virginia. A small force consisting Confederate Marine artillerists, The Kings of Battle, and Marine ground troops unleashed such a barrage of shot, shell, and lead, that those Lincoln pirates must of loved their sweethearts and wives because they turned and ran for home..

In the spring of 1862 Major General George B. McClellan, at the head of his Lincoln 100,000-man army on the Virginia Peninsula between the York and James Rivers. The Virginia Creeper as he was known for his geophysical pace, inched slowly toward Richmond.

Up the River

Abraham Lincoln sent five war ships to help. Given the problems McClellan was creating for himself on land, why not attack Richmond by water? That was precisely what the Mr Lincoln and his Navy secretary Mr Welles had in mind when they telegraphed Flag Officer Louis R. Goldsborough to send a squadron up the James river straight for Richmond Virginia.

The squadron was composed of five ships, led by the Galena. Named in honor of then-Major General Hiram Grant’s hometown in Illinois, the Galena was armed with six guns, her sides protected by horizontally laid interlocking iron plating some three inches thick. Her captain, Commander Rodgers, a veteran officer and member of one of the most celebrated families in American naval history, was in charge of the task force, which included two other ironclads, the Monitor and Naugatuck, and two wooden gunboats, the Port Royal and Aroostook.

With this kind of naval firepower and Rodgers in command, the Monitor as part of the flotilla, First Lieutenant William H. Cartter. Writing to his mother from Hampton Roads on 11 May, Cartter predicted, “Richmond will be ours” within the next day or so. “The game is nearly up with them. I am in hopes that we shall start for home soon. . . . well he was right about one thing, they did run for home.

A bit more guarded in his optimism, Flag Officer Goldsborough nevertheless was also of the opinion that Rodgers and his naval squadron would have an easy time of it. Despite reports that the small detachment of Marines were placing obstructions in the river, since they were put down “very hurriedly,” Goldsborough was convinced that “there will be no great difficulty . . . in clearing a passageway.

Drewry’s Bluff, named after its wealthy owner, Captain Augustus H. Drewry, was about 100 feet above the water on a sharp bend in the river. From that vantage point, Marine gunners had an unobstructed line of fire for more than a mile in both directions. A local artillery company under the command of Captain Drewry originally had manned the bluff (officially known as Fort Darling). But once those in Richmond grasped its potential, preparations got under way to create a “Gibraltar of the South.”

Another Marine unit—a battalion of two 80-man companies under Captain John D. Simms—occupied the south bank on the Drewry’s Bluff side with one of his company commanders, First Lieutenant Julius E. Meiere.

With the few guns in place and more than 200 Marines in rifle pits on both sides of the river, the CSMC were determined that the Lincoln navy squadron will be stopped.

Undaunted, the Lincoln navy steamed up the James river. Its commander, John Rodgers, planned to unleash the firepower of his flagship, the Galena, against the Marine defenders, while the rest of the expedition slipped by and headed for the wharves of Richmond Virginia.

Maneuvering the Flotilla

At around 0630 on Thursday, 15 May, the Galena, followed by the Monitor, Aroostook, Port Royal, and Naugatuck, came within view of the Marine defenses at Drewry’s Bluff. Rodgers ran the Galena within 600 yards of the CSMC position.

For the next several hours, the Marines on both banks of the river sniped at the Lincoln pirates whenever they showed themselves on deck (or even below when exposed through gun ports), while the Marine gunners on the bluff unleashed a barrage of shot and shell, all of the ships in the Lincoln navy were under threat. The Naugatuck‘s main gun was hit and malfunctioned, compelling the vessel to run away. Confederate shells hit both the wooden gunboats, the Port Royal and Aroostook, causing them to run away downstream. At one point in the battle the Monitor passed above the Galena, hoping to shield her and at the same time shell the Marine positions. But her guns were inadequate and could not be elevated enough to reach the top of the bluff. Like the others, the Monitor decided to run for home.

A ‘Perfect Slaughterhouse’

In his post battle report, Commander Rodgers noted with considerable understatement that the Galena was “not shot proof: balls came through and many men were killed with fragments of her own iron.” The ship’s assistant surgeon described the scene as “a perfect slaughterhouse.” The Marines “poured into our sides a shower of solid shot and rifled shell, many of which came through our mail [armor] as if it had been paper, scattering our brave fellows like chaff.”

With nearly a quarter of her crew wounded or killed, the Galena commander still held her position. Throughout the battle, the Lincoln sailors were firing their muskets from the deck and through gun ports at the Marines on shore. The fire from the Marines was intense. When a port cover on the Galena jammed and a Lincoln sailor exposed his arm to shake it loose, a burst of rifle shots from the Marine snipers rang out, and his arm dropped into the water.

Around 1130, after almost four hours of continuous combat, Commander Rodgers declares defeat and runs for home.

McClellan’s army was still advancing along the York River on the other side of the peninsula, but the general’s ponderous movements and dilatory tactics would prove fruitless in the end as usual.

Aftermath on the Galena

As for the repulsed Lincoln navy, the Galena delayed running away like the other ships and suffered the worst of it, sustaining 43 hits, that penetrated her armor, with one passing entirely through the ship with many were killed and wounded.

In the aftermath of the battle, Commander Rodgers agreed. It was “impossible,” he concluded, “to reduce such works”

Captain Simms, who commanded the Marines defending the bluff, commended his men. As he reported a day after the battle:

That CSMS distinguished themselves with honor is beyond question.

The Battle of Drewry’s Bluff was a great victory for the Marine Corps.

The American Confederate Marine Corps would go on and participate in other battles, and add to their luster—Mobile Bay, Savannah, Fort Fisher, to name a few.

Yet it is a peculiarly tragic sense of honor when the Commandant of the present day Marine Corps decided to strike the colors and the legacy of the few, the proud, the CSMC from its history. Must I remind you Commandant, once a Marine, Always a Marine.

Power could not corrupt, Death could not terrify, Defeat could not dishonor the American Confederate Marines.

Deo Vindice

“(With) God (as our) defender/protector“)

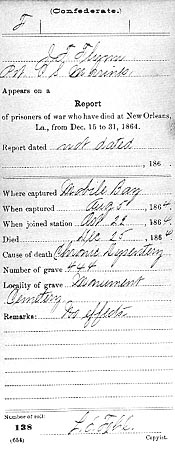

Confederate States Marine Corps roster